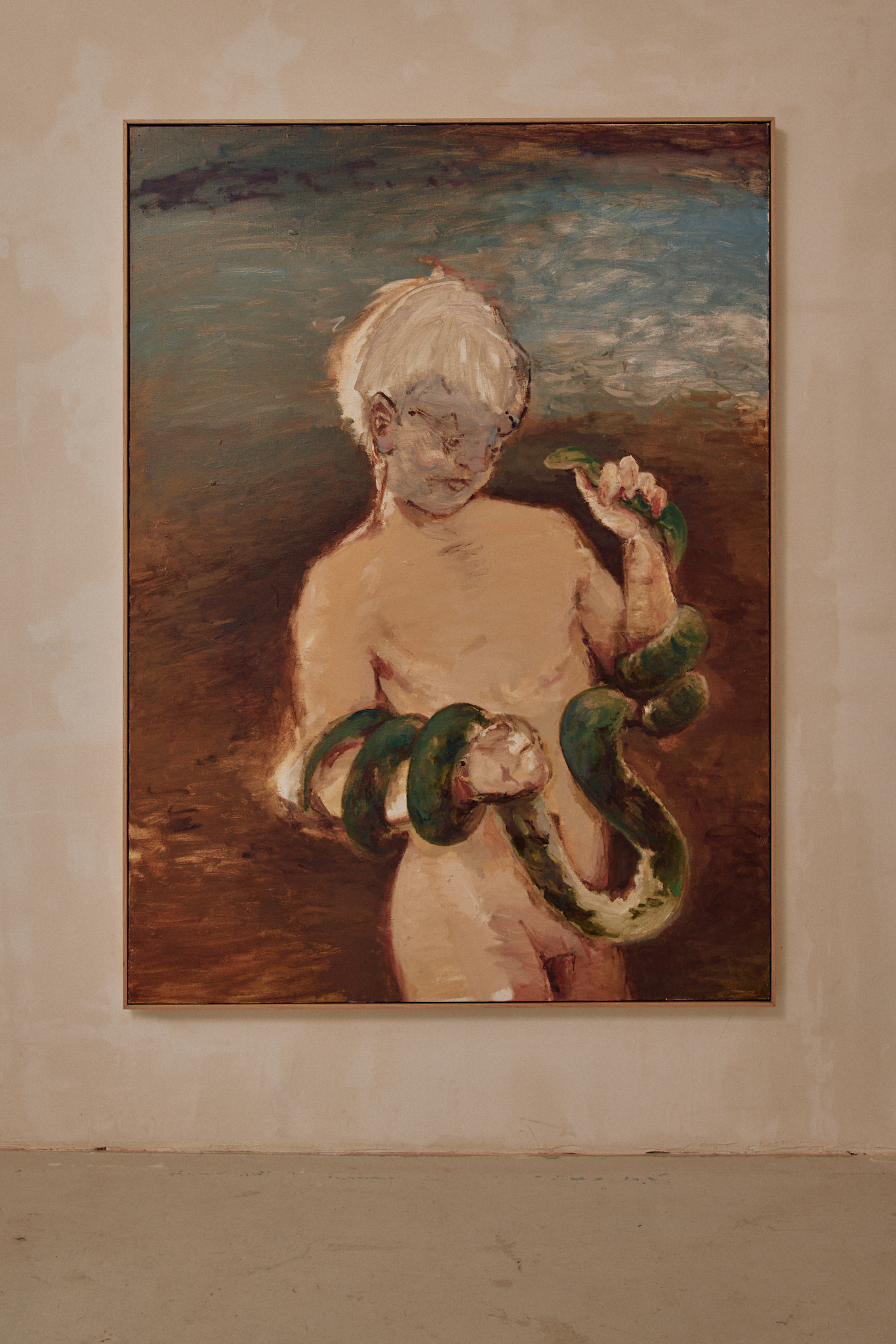

“Time plays an increasingly larger role, or reoccurring theme within my work,” said Nicholas Ives in the catalogue for an earlier iteration of the Saturn Devours series of works – “my recent experience of becoming a father has heightened this awareness of my place within a changing and transitional and transforming world, as does my work teaching drawing from cadavers within the dissection suite at university. These meditations upon life, death and absurd play between these pivotal poles of existence and being.

Ives is a painter who, unusual these days, is actually in love with painting, and as his technique grows ever more sophisticated, the thematic elements grow deeper and more philosophical. He is apainter’s painter. His work is intensely human, defying abstraction and mediating between the vicissitudes of process and the deeply intimate. He continues to explore the infinite possibilities ofpaint as a vehicle for life and each new phase disrupts the last.

Ives is a painter who, unusual these days, is actually in love with painting, and as his technique grows ever more sophisticated, the thematic elements grow deeper and more philosophical. He is apainter’s painter. His work is intensely human, defying abstraction and mediating between the vicissitudes of process and the deeply intimate. He continues to explore the infinite possibilities ofpaint as a vehicle for life and each new phase disrupts the last.

‘Hyposubjects’ 2022

oil on linen, framed.

33cm x 25cm

AUD 2,500

SOLD

Nicholas Ives

SMILE

192cm x 300cm

Oil on linen

$12,000 AUd

Nicholas Ives

For No Reason

(Doug Moran Finalist )

136x150cm

Oil on linen, framed

$8000, inc GST

SOLD

Nicholas Ives

I Don’t Know

136x150cm

Oil on linen, framed

$8000, inc GST